Truth or Treason?

How Trump’s war on journalism has reached new heights

If you’ve been keeping up with the battle between President Trump and the press, you’re probably aware of his Twitter tantrum about journalists in early September.

On Sept. 5, the New York Times published an anonymous op-ed written by a senior White House official titled, “I Am Part of the Resistance Inside the Trump Administration.” The official said they are a part of a discreet movement within the administration to reduce any political damage that the president might inflict.

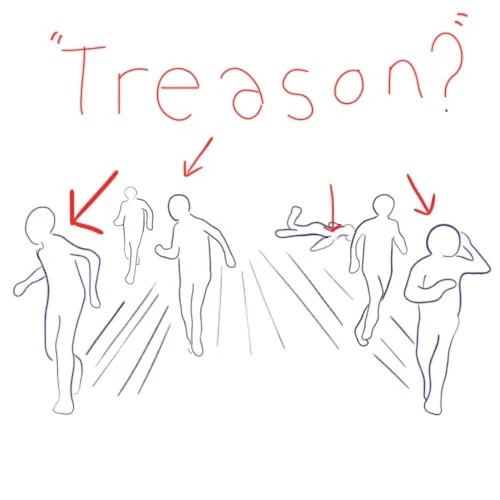

Illustration by

The author called President Trump’s leadership style “impetuous, adversarial, petty and ineffective,” and said that meetings with him not only swerve off track but often include “repetitive rants,” and that the president’s “impulsiveness results in half-baked, ill-informed, and occasionally reckless decisions that have to be walked back.”

In response, Trump flew to his beloved social media platform and released this intellectually stimulating tweet: “TREASON?” (Perhaps not the best choice of punctuation. It sounds like he’s questioning what treason is, which, frankly, would explain a lot.)

While not an uncommon word in President Trump’s rather limited vocabulary, there seems to be quite a disparity between the actual definition of treason and Trump’s definition. Article III, Section 3 of the Constitution says, “treason against the United States shall consist only in levying war against them, or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort.” Disloyalty, perhaps, but certainly not treason characterized this op-ed. The constitutional definition was worded this way specifically to deter people from using the term loosely or for political reasons, which is exactly what President Trump uses it for.

In Trump’s dictionary, ‘treason’ appears to refer to anyone who questions him, his actions, or just generally anything he says. As the leader of the country, he is supposed to set an example for citizens. Careless use of such a serious term sends the message that people can use it to describe anything they feel personally wounded by. This strongly affects the credibility of the media in the eyes of citizens; if the president can characterize that anonymous op-ed or an entire news outlet such as The New York Times as treason, what’s to stop him from discrediting journalism all together?

Trump angrily constructed a couple more tweets about “The Failing New York Times,” calling their sources “phony” and demanding the “GUTLESS” senior official be turned over.

As for The New York Times and their “phony” sources? Barely three days following his tweets bashing NYT’s credibility, Trump tweeted out a quote about his presence in the Republican party from reporter Nicholas Fandos of The New York Times. “So true!” he captioned it. So now he believes The New York Times is a credible source? His indecisiveness just solidifies the idea that Trump judges what is credible and what is not solely based on how he is portrayed in it.

Whether or not you agree with the anonymous authorship or this essay being published in the first place, no treasonous action occurred here. What did occur was the exercise of First Amendment rights. An articlefrom “The Atlantic” discusses Trump’s “lexical influence” and whether the president’s words matter, as the general strategy surrounding his shocking and often offensive statements has been to dismiss them. The article asserts that, on issues across the board, “Trump’s words have the power to cleave public opinion, turning nonpolitical issues into partisan maelstroms and turning partisan issues on their head,” which has resulted in even further polarization of political parties.

The article also references a study from The Washington Postlast winter that showed 42 percent of Republicans believe that news portraying politicians or a political party in a negative light is always “fake news.” Let’s consider that for a moment. Nearly half of the Republican party has been persuaded to completely dismiss any news that contains something they might not want to hear. This concept of “fake news,” as well as other ideas Trump’s administration has coined, such as “alternative facts,” have come about solely through Trump’s words, the article contends. The article concludes with the warning that “it would be a mistake to conflate Trump’s indolence for ineffectiveness,” and the claim that no matter how often they are disregarded, Trump’s words matter.

Some language expertsspeculate about Trump’s speech. Richard Wilson, a professor of anthropology and law, said that some public figures use language in this way to set themselves apart from others. It makes some citizens feel less like they are being talked down to by someone who is extremely different from them. Edward Schiappa, a professor of rhetoric and media at MIT, said Trump’s way of communicating also simplifies complex political concepts (to an extreme) that may make people who are not knowledgeable on the issues feel like they understand them. This gives audiences the idea that he is different than politicians before him, which is what many want. When Trump repeats the same, simple phrases over and over again about an issue, people may be more inclined to believe it. Schiappa said he believes Trump’s rhetoric is so concerning to critics because “his words suggest a very simplistic mind that may not be up to the challenges of the presidency in the 21st century.”

We are living in a very momentous time in journalistic history—a time when an administration has completely convinced their following to dismiss any news that does not bolster or adhere to their political values and agenda. But those who understand journalism, and I mean actuallyunderstand it—the processes, the rules, the ethics, the details, the immense amount of thought and work that goes into every part of it—know that fake news does not simply come about as Trump would have you believe.